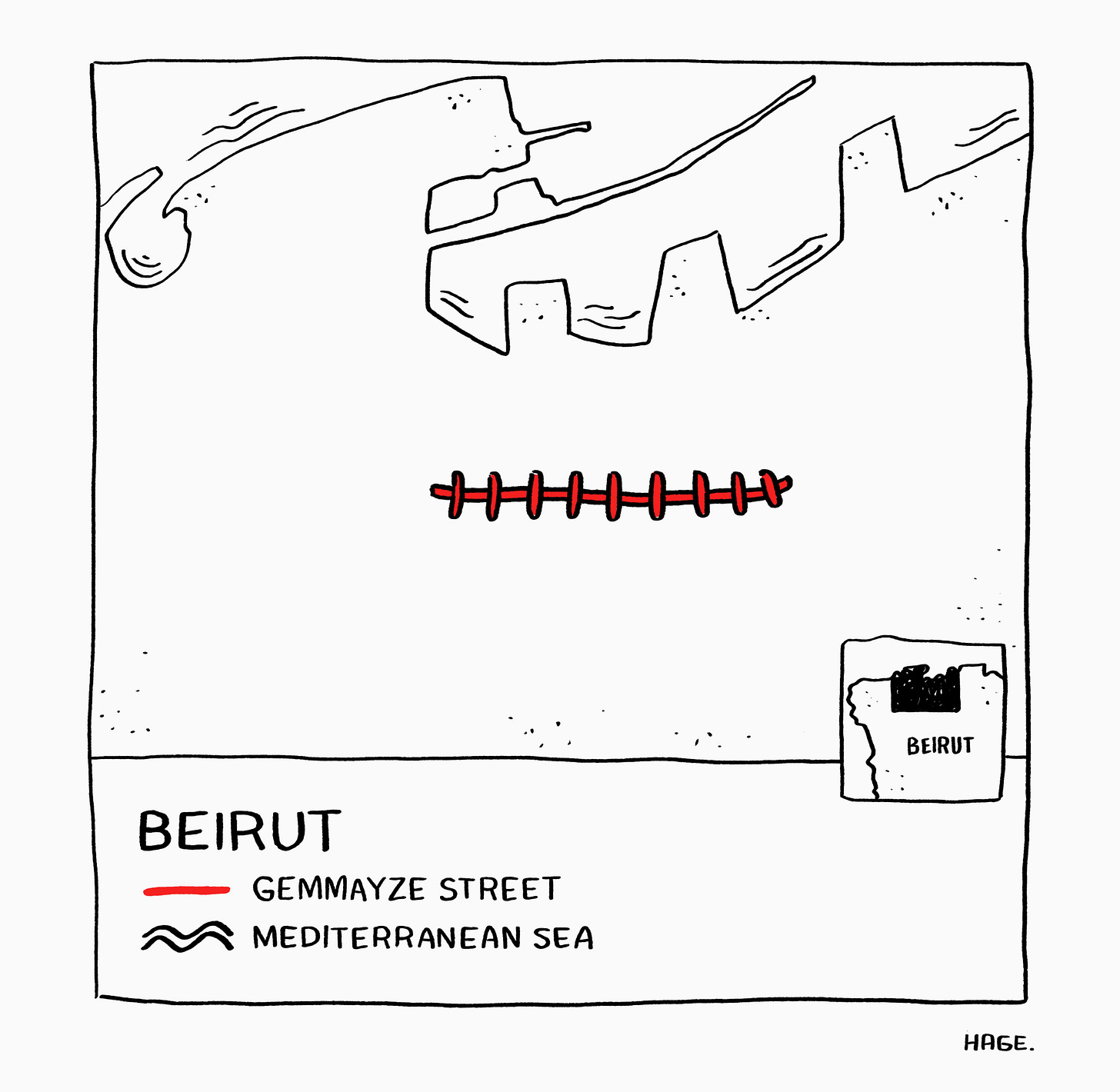

Gemmayze

Issue 018

I just got back from a three-week visit to Lebanon—the longest I’ve stayed since I migrated. The first time I visited Beirut after leaving, my stay was so short I greeted everyone with goodbye.

Each time I go, I add a few extra days to ease into the mood—like slowly reacquainting myself with a friend I once unfriended mid-argument.

So three weeks is impressive, considering the conditions under which I left, and the rather dramatic breakup the country and I had at the time.

As you land in Beirut, you notice a thick black smog over the coast. By the time you leave the airport, you realize it’s not pollution—it’s collective thinking. The mindsets are darker, the drivers angrier, the familiar faces gone. And the strangers have stopped smiling.

And honestly, I don’t blame them. They’ve endured a financial collapse, a political meltdown, a pandemic, the biggest non-nuclear explosion in modern history, and a brutal war—all within five years, with no intermission. Personally, I made it through the first act, then quietly slipped out in 2021 before the encore, while they stayed for the full, brutal run. So yes, they’ve earned the right to their current behavior, and they have my full respect for still standing. That said, I’m going to be selfish and focus on how it felt to me, because objectivity is so overrated.

I’ll start with Gemmayze—a street in Beirut that’s part residential, part commercial, and entirely personal. It’s known for its bars, restaurants, cafés, and galleries, but to me, this street is where most of my early story played out.

My school, Sacré-Coeur, sat right across from Damas bakery, which made skipping class dangerously convenient. We’d often sneak out for a Manoushe that made the rest of the day feel optional. Gemmayze is where I had my first whiskey, at a bar called Cactus—back when it was the only bar around, before the whole street turned into a confused Soho on Arak and identity issues. I had my first date there. My first crush. My first kiss. I test-drove every bad pickup line I could come up with. Some even worked. I had my first art exhibition on that street, at Artlab gallery, held my first protest, and sat through my first serious business meeting—sandwiched somewhere between mezze and more whiskey. I ate my favorite meals, drunk-argued with valets, and met some of the best people I know.

You see, memory doesn’t always live in the mind. Sometimes it clings to objects—a photo tucked in a wallet, a T-shirt you never returned, a letter from someone who’s now a stranger. For me, the first three decades of my life are scattered across this street—stitched into its buildings, bars, staircases, and corners. When the Beirut Port Explosion hit, it didn’t just destroy walls and windows. It tore through the places where my memories lived. My bond with the street frayed, and with it, my sense of belonging.

Coming back to this street a few years later and seeing new bars, cafés, and restaurants sprouting along its sides like wild fungus, stirred something I couldn’t quite name. On one hand, of course new places would open—what did I expect? Reconstruction breeds reinvention. But wandering through all that polished newness, through hip spots I instinctively and emotionally rejected for not reflecting the real spirit of Gemmayze, left me uneasy.

I couldn’t tell if it was the places themselves, or the fact that most of them were empty. And the ones that weren’t—I didn’t recognize a single soul. Which, in a city like Beirut and a street like Gemmayze, is statistically suspicious. You’re supposed to run into your ex, your aunt, and your childhood schoolteacher before you hit the next block. But this time, most faces were strangers.

It felt like a whole new generation had been waiting for us to clear the stage—and now that we have, they’ve come out of hiding. And that’s fine, I’m not criticizing. I’m just quietly stunned by the fact that I’ve become a tourist in a street I once walked with my eyes closed.

Fellow diaspora, what do you do when your past city feels like someone else’s future, and the one you moved to still feels like a hotel lobby?

Personally, I’ve come to terms with the fact that I’ll have to learn to live boneless—without a spine to lean on. Just a soft, floating body drifting between zip codes.

Here are a few thoughts from someone trying to make peace with homelessness:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Private in Public to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.